Recent volatility in the hog market has been both a blessing and a curse for producers trying to navigate the current environment as they evaluate risk management decisions. On the one hand, profitability projections are as strong as they have been since the PED year in 2014, in some cases exceeding what was available at this point of the year for those particular periods. Assuming hog prices and feed costs stay at these levels into next year, the industry looks to be extremely profitable. On the other hand, there is massive uncertainty surrounding the extent and duration of potential additional pork exports to China as well as whether or not ASF eventually spreads to the U.S. This uncertainty has sharply raised volatility in the hog market, which has led to a surge in the cost of option premium for producers.

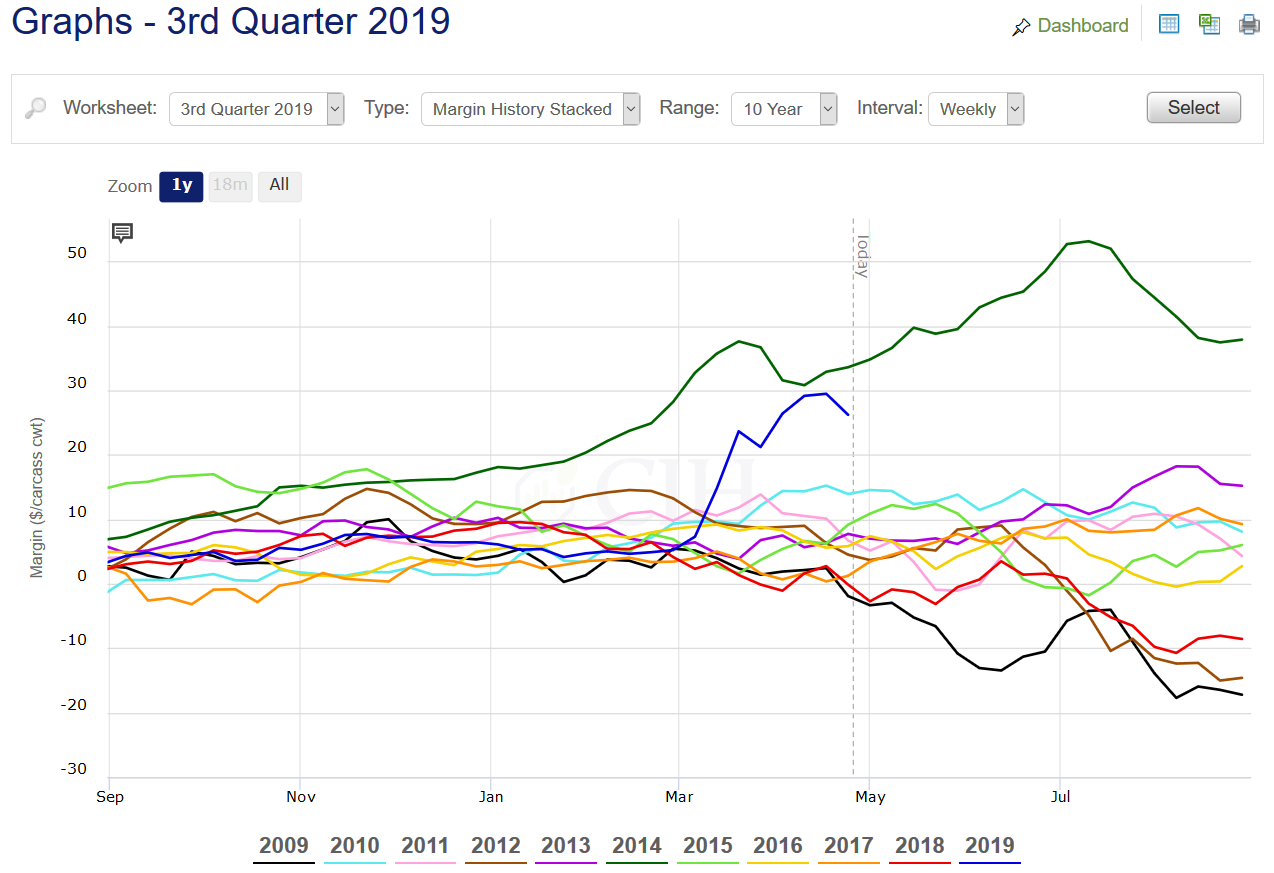

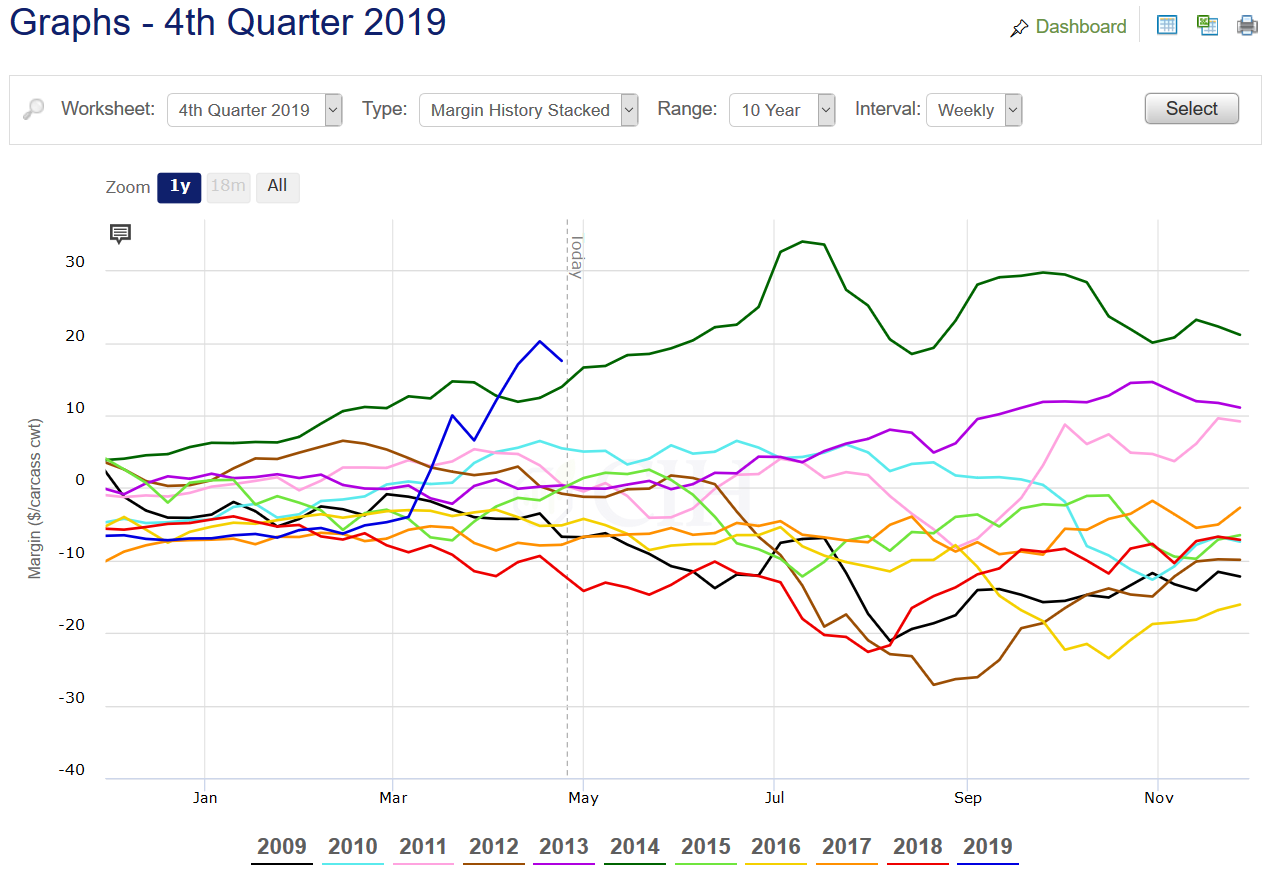

While hog producers realize the opportunities that currently exist to capture forward profitability and are keen to protect margins following a very difficult market throughout 2018 into early 2019, they understandably are concerned over the potential for further price increases. Recent industry estimates suggest that China’s pork production this year could drop 30% from 2018, with the extent of that loss 30% larger than the annual production in the U.S. Moreover, it has also been mentioned that the regional fallout will take years to correct, making this a long-term structural issue that will disrupt global trade and the supply chain. Figures 1-3 show the current projections for forward hog margins in Q3, Q4 and Q1 of 2020 relative to the past 10 years.

Sky High Option Volatility

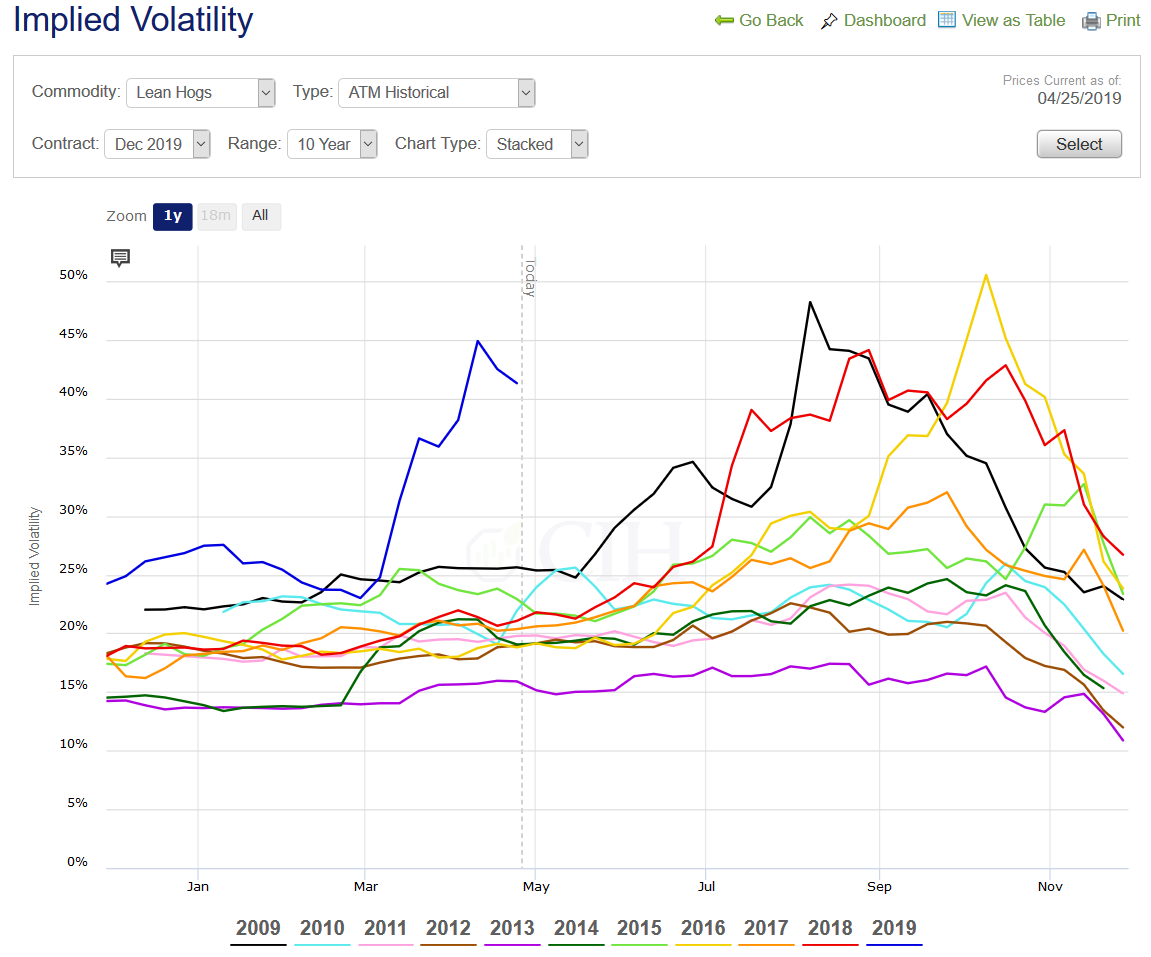

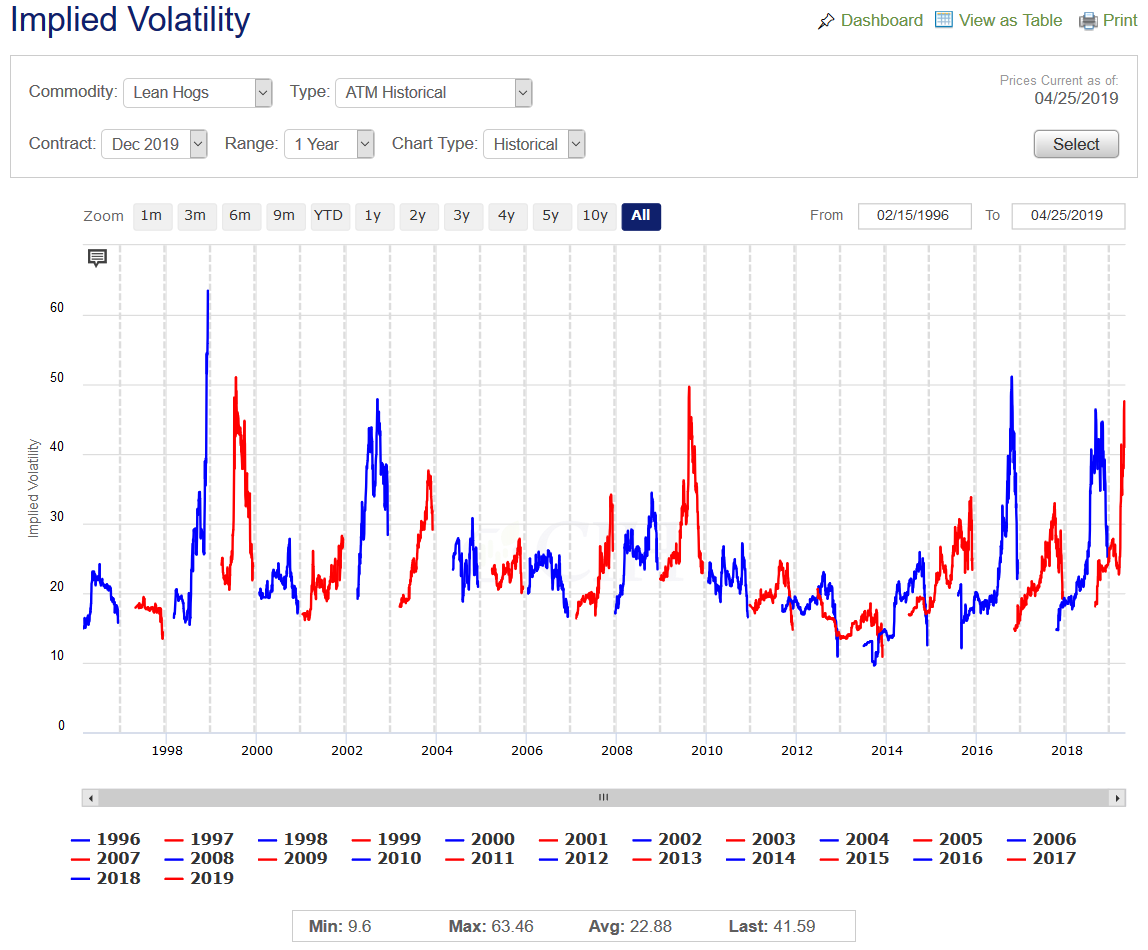

The surge in projected margins from mid-March into mid-April due to a sharp rally in hog futures that was partially aided by a concurrent drop in in feed costs, also accompanied a significant increase in hog option volatility. Looking at the December Lean Hog Futures contract, implied volatility recently spiked to 45% and very close to the near 50% levels achieved in 2009, 2016 and 2018, although it should be pointed out that in those years, the spikes occurred much later and closer to expiration. Also, notwithstanding the 1998 December hog market when option volatility spiked to over 60% during the extreme price meltdown in that year’s Q4, 50% has historically been the peak for implied volatility in December hog options (see Figures 4 and 5).

Certainly part of this year’s spike in volatility can be attributed to the sharp move in futures from early to mid-March. The June contract ran $20/cwt. from around $75 to $95 in the span of just 2 weeks, as the market adjusted to new information quickly. The move was similar to a run-up in the 2014 market, when June futures rallied from around $110 to over $130 in a comparable span of time between late February and mid-March (see Figures 6 and 7).

As a result of the increased volatility, option premiums have become much more expensive. As an example, December hog at-the-money options are currently trading over $10/cwt. Even August hog options that are closer to expiration carry at-the-money premiums over $8/cwt. These are about double what they were prior to the volatility spike in March, when option volatility was already quite expensive within a historical context.

Risk Management Implications

With strong forward profit margins that extend well into 2020 and following on what was a very poor period for profitability over the past year, reducing risk in this environment is prudent. The best way to go about that however is complicated to say the least. Ideally, a hog producer could simply purchase puts on their projected production to place a floor under the market, leaving all the upside open to hopefully achieve windfall profits if prices continue surging higher. The problem with that is the significant cost associated with retaining that much flexibility. Using December as an example, the $10/cwt. cost of an at-the-money option is currently more than half the actual margin that is there to protect. Given this prohibitive cost, producers are exploring ways to strike a balance between keeping upside opportunity open while also protecting downside risk.

Some may still feel that buying puts outright makes sense in the present environment, and there is certainly room for volatility to increase further. Also, if the puts are for a deferred production period, there is sufficient time to eventually reduce that expense by selling other options against those puts to create lower-cost spreads. The problem though is that implied volatility is already high, so if you are just buying puts, you are purchasing an inflated asset that could see its value erode quickly if the volatility begins to come out of the market. So while buying outright puts on a portion of one’s production probably makes sense, it maybe shouldn’t be the only alternative considered.

One thing to keep in mind is how strong margins are currently projected within a historical context. At the 95th percentile of the previous 10 years, hog producers have only made more money than this around 5% of the time over the past decade. This is significant and should not be overlooked. Perhaps it would be wise to just take these very strong margins on a portion of one’s forward production and eliminate that risk altogether. You might simply ask yourself what percentage of your production is ok to accept current margins on, and remove that piece of risk from the total exposure pool.

As another example, some producers may want to put a floor underneath the current market and may be ok with giving up some of the current margin to maintain opportunity for higher prices to a degree. By accepting a cap or price ceiling above the market, they can assure themselves a floor that will still allow a profitable margin to be realized in a worst-case scenario, but allow for stronger margins in a best-case outcome. Again, this might apply to a portion of the overall production, but not the whole thing. A lower cost way still might be to only protect a range of lower prices below current levels while also accepting a price cap above the market. The benefit with this approach is that it might allow a producer to start the protection closer to the market, and/or use a higher cap for their ceiling. It also takes advantage of the high volatility environment by receiving more credits from selling options. Here also, this would probably be appropriate for some but not all of one’s total risk exposure.

Finally, some might be fine selling at current price levels, but want to retain opportunity for prices to continue rising further. Here, a producer might consider buying call options against a portion of their sales in the futures market or the cash market to create some degree of participation in higher prices. The call options might be purchased “out of the money” such that the upside participation doesn’t begin right away, but kicks in should a significantly higher price outcome eventually be realized. The benefit with this approach is that a producer might feel more comfortable locking in a larger percentage of their production with the margins that are currently available, knowing that some of this production will be open to participate in a sharply higher market.

Portfolio Approach to Risk Management

What this amounts to from a practical standpoint is using a mix of different contracting alternatives to protect current margins. This spreads the risk that any one price or margin outcome will negatively impact profitability if a variety of different strategies are employed at the same time. Just like a portfolio manager will use a mix of stocks, bonds, and cash to construct an asset allocation that allows an investor to realize their long-term goals, this approach to risk management might be a good way to hedge against different outcomes or scenarios.

If volatility plummets, having part of the risk management portfolio comprised of futures or cash sales along with short volatility option positions will limit the damage from the portion that consists solely of long puts or call options purchased against futures. If volatility continues to rise, the portion of the portfolio consisting of outright long options will benefit. From a price standpoint, having a decent percentage of one’s production floored will guard against a sharply lower price scenario, such as in the event of an ASF outbreak in the U.S. At the same time, leaving upside open on a percentage of the total production will hedge against a higher price outcome in a sharply rising market.

In the investing world, passive strategies have become very popular, such as index funds that track the broader performance of the market against a benchmark like the S&P 500. Some investors will allocate a portion of their stock portfolio to simply track the market, while allocating other strategies to sectors of the market they feel will outperform given the current point of the economic cycle. Perhaps staying open on a portion of one’s production might also be a choice within a risk management portfolio, such that the performance of this piece will track whatever the market eventually does.

One good question to ask in deciding on the balance of various strategies that would work best for your particular operation is this: “what percentage of your production do you want to have floored (to secure current profitability), and what percentage are you comfortable having capped?” This certainly does not have to be the same number, but answering that question can go a long way to helping you determine what mix of strategies may be a good fit for your particular goals and circumstances. While the current market environment definitely presents challenges in managing risk, the good news is that there are strong margins to manage, and this reality should not get lost in the discussion.

For more help on evaluating specific strategy alternatives or to review your operation’s risk profile, please feel free to contact us.

There is a risk of loss in futures trading. Past performance is not indicative of future results.